From the June 1980 issue of Car and Driver.

We made it from Atlanta to Dallas in twelve and a half hours. But that was because we were just cruising, you know, taking in the scenery and enjoying the local color. Besides, we got stuck in bumper-to-bumper camper traffic all the way to Birmingham. Some big collegiate sports event was under way—the University of South Carolina versus Alabama’s Crimson Tide in a varsity dogfight, to judge by the fans.

No, no, I won’t make fun of those good old boys in their Winnebagos driving since dawn with their good old families all the way from Columbia and Charleston and Beaufort just to root for the team of their choice. No, I won’t crack wise about the denizens of that fair corner of the free world, because I feel too good about Western civilization. And the reason I feel too good about Western civilization is that there I was a living, breathing part of it, in the best damn car I’ve ever driven, smack in the middle of the best damn country there’s ever been on earth. And, also, because cutting in and out of those giant travel homes at a hundred miles an hour is more fun than a Marseille shore leave, and hardly anybody riding in them threw beer cans at us either. Zoom, zoom, zip, zip, I couldn’t have been happier if I’d had a sack full of Iranian radicals to drag behind me.

And they love cars down there. Love ’em. The men look, and the women look, too. And they smile with honest pleasure just to see something that dangerous-looking doing something that dangerous. But best of all the looks we got were the looks we got from the ten-year-old boys. They’d be back there with their little faces pressed against the glass in the RV back windows, and they’d see this red rocket sled coming up behind them in the $50 lane. It couldn’t help but touch your heart, how their eyes lit up and their mouths dropped down, as if Santa’d brought them an entire real railroad train. You could all but hear the pitter-patter of the sneakers on their feet as they ran up front and started jerking on their dads’ Banlon shirt collars, jumping up and down and yelling and pointing out the windshield, “Didja see it?! Didja see it, Dad?! Didja?! Didja?! Didja?! Didja?!“

We came by a 930 Turbo Porsche near the Talladega exit. He was going about 90 when we passed him, and he gave us a little bit of a run, passed us at about 110, and then we passed him again. He was as game as anybody we came across and was hanging right on our tail at 120. Ah, but then—then we just walked away from him. Five seconds and he was nothing but an overturned-boat-shaped dot in the mirrors. I suppose he could have kept up, but driving one of those ass-engined Nazi slot cars must be a task at around 225 percent of the speed limit. But not for us. I’ve got more vibration here on my electric typewriter than we had blasting into Birmingham that beautiful morning in that beautiful car on a beautiful tour across this wonderful country from the towers of Manhattan to the bluffs of Topanga Canyon so fast we filled the appointment logs of optometrists’ offices in 30 cities just from people getting their eyes checked for seeing streaks because they’d watched us go by.

Don’t get me wrong; we weren’t racing. This was strictly a pleasure drive. We had a leisurely lunch in Tuscaloosa, had long talks with every gas-station attendant we saw (and at about nine miles a gallon with a nineteen-gallon tank, we saw them all), and ran into some heavy rain in Louisiana, too—had to slow down to practically a hundred, as it was a two-lane road. And then in Shreveport we had a big steak dinner with lots of cocktails and coffee and dessert and Remy Martin. Why, really, we just strolled into Dallas on that third day of a week during which I had more fun than I have ever had doing anything that didn’t involve young women. And this kind of fun lasted longer. And I never fell asleep on top of it once.

Actually, the trip didn’t start out all that well. The idea was . . . well, I’m not quite sure what the idea was. But Ferrari North America, which is based in Montvale, New Jersey, had a 308GTS that needed to be delivered to Los Angeles by January 2, to be featured in a movie. Ferrari called Car and Driver and asked if they’d like to assign someone to drive it across the country. Car and Driver was good enough to ask me, and of course I said yes. But I had misgivings. Like anyone who loves cars, I’d been fantasizing about Ferraris since before I knew how to say the name. Fur-rare-ies, I thought they were. But in my imagination they still all looked like Testa Rossas. In recent years they’d gotten a bit beyond me; I didn’t know what to make of these modern pasta-bender luxo-boxes with price tags in the early ionosphere. They have their engines in sideways and backwards, and you sit down on the floor where you can’t see your fenders, your feet, or the road. Or that’s the way they seemed to me when I sat in one at the auto show, which was the only time I ever had sat in one. And because they were so funny-looking, I assumed they were hard to drive. Besides, I’m opposed on principle to things with wheels that cost more than $20,000 and don’t have “Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe” written down the side. Why, there are people starving in Italy. Or going hungry, anyway. Well, maybe not hungry, but I’ll bet they don’t have enough closet space and the kids have to share a bedroom.

And I had some other problems, too. I have a daytime job where I’m editor of the National Lampoon and I had fallen grievously behind in potty jokes, racial slurs, and comments that demean women. Deadlines loomed, the art department was in a pet, and down at the printing plant they were snarling in their cages. I had no business taking off just then to go do something silly in a rolling red expense account.

So I wasn’t as enthusiastic about this project as I might have been, especially when I had to go tell my boss, the president of the National Lampoon‘s parent corporation, that I had chosen this extremely inconvenient week to go on a cross-country screw-around for the benefit of another magazine. Now this boss of mine, Julian Weber, is a cold, taciturn, hard-eyed Harvard Law School graduate, about 50 years old, always dressed in a suit, and a very square sort of fellow. And as I was standing in front of his desk, backing and filling and making up lies, he began to frown with great concentration. What I was saying was, “I know it doesn’t seem like I’ve been here very much lately but I’ve . . . uh . . . been working at home a lot,” but what I was thinking was where I could get the boxes I would need when I cleaned out my desk.

Then he blurted it out: “Can I go, too?”

The next thing I knew, I was sitting in the parking lot at Ferrari, sitting way down on the floor of this $45,000 atomic doorstop, completely puzzled by the controls; and sitting rather stiffly in the bucket seat next to me was my goddamned boss. At least he had a pair of blue jeans on, but his blue jeans had been pressed, with a perfect crease across each knee. I don’t know if they sell blue jeans at Brooks Brothers, but if they do that’s where he’d bought these.

I couldn’t figure out what it was going to be like, cooped up for a week in a car with somebody and unable to discuss drugs or women. I also couldn’t figure out how to work the car. Everyone at Ferrari was on Christmas vacation; the keys had been left with the receptionist. There wasn’t even anyone there to look properly worried, let alone to show me how to start the thing. And the Ferrari manual was translated from Italian to English by someone who spoke only Chinese. “Well,” said Mr. Weber, “I’m ready to go now.”

I remembered that Bill Baker, Ferrari’s director of public relations, had told me, “Be sure not to –––– or you’ll foul the plugs.” But what it was that I wasn’t supposed to ––––, I had no idea. So, finally, I just started it up and very tentatively, very nervously drove it out onto the Garden State Parkway, where the plugs immediately fouled. We coasted onto the berm. I got the car started again and out into traffic and it loaded up and stalled. I got it started another time and it began to misfire and choke, and I had to stick it in third and run it up over five grand just to keep the engine moving.

“I thought you knew how to drive one of these,” said my boss. And I had to keep it in third all the way to Trenton before the plugs cleared. A solid wall of dirty traffic was pressing in from every side while I sat perspiring, not a fender in sight, waiting for some jackass in a Peterbilt to make a belly tank out of us. I got off the turnpike at Wilmington and headed down the Delmarva Peninsula. The car seemed to be running all right, but now Julian wanted to drive. I was afraid that, if he didn’t keep the revs up, we’d stall again, and I couldn’t explain to him how to drive the car because I hadn’t the slightest idea myself, and, besides, I just didn’t feel like riding along at 55 with this lawyer type at the wheel telling me how foreign cars of this kind seemed “quite unusual in their method of operation” or some such. I mean, Julian’s a New Yorker, and New Yorkers think all cars are yellow and have lights on the roof. So I held him off down past Dover, but he was beginning to insist, and he’s my boss, and what could I do?

We had just turned off onto Route 1 along Delaware Bay when I put him behind the wheel. Route 1 is a brand-new road, four lanes wide and butter-smooth, built to carry hordes of picnic-prone Wilmingtonians down to the ocean shore. But in December there’s nothing and nobody in sight. Julian settled into the driver’s seat and gave the Millennium Falcon–like controls a momentary glance. Then he stamped on the accelerator with an expensive loafer and redlined the 308 up through the gears to a hundred miles an hour through the potato fields and abandoned burger stands without time to even take his hand off the shift lever until he hit fifth, and when he did have time to take his hand off he used that hand to plop a Blondie cassette into the Blaupunkt and a quarter-ton of decibels came on with “Die Young Stay Pretty,” and the scenery exploded in the distance, bush and tree debris flying at us while my eyeballs pressed all the way back into the medulla, and that quadruple-throated three-quart V-8 wound up beyond the vocal range of Maria Callas, Eeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee, leaving, I’m sure, a trail of shattered stemware in the more prosperous of the farmhouses we passed along our way.

And so it was Julian, my sobersided superior in the corporate hierarchy, who turned out to be the real leadfoot. He spent his half of the driving time doing a very credible imitation of Wolfgang von Trips, while I spent that half of the driving time nervously looking for cops. He turned out to be a pretty good guy, too, for a lawyer. (Although, to protect his marriage and business career, his views on drugs and women will go unrecorded.) Anyway, it was that moment out on Delaware Route 1 that changed the entire complexion of the trip.

I guess what we were supposed to be doing with the car was to see if it could perform the function for which it was built. That function is high-speed touring, and the answer is YES, carved in those monumental granite letters that once were used for the title frames in movies like El Cid. The Ferrari isn’t much to bop around town in. It’s necessarily stiff and uncompromising at low speeds. And you’d sooner dock a sailboat in a basement utility sink than try to parallel-park it. But turn the son of a bitch loose on the open road and it’s as though you’ve died and gone to hot-rod heaven. True, the 308 wasn’t designed, really, for American touring, where the speed limit is 55 and distances are measured in thousands of miles instead of hundreds of kilometers. There’s nary a gear in the box where the Ferrari will do 55 with pleasure, and the luggage space wouldn’t make a good ice bucket. But the answer to those complaints is, Who gives a good goddamn? You drive this car for an hour, a hundred miles down the coast between the dunes, with the cattails waving in the tidal marshes and the winter surf crashing on the sea walls, through a blur of empty resort towns with the afternoon sun down low and Edward Hopper-bright across the landscape—you do that for an hour and you’ll kill for this car. You’ll murder people in their beds just to get back behind the wheel.

And we slipped down the eastern shore of Maryland, on into that tag end of Virginia below Assateague Island, and out onto the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel, nearly as awesome a piece of engineering as what we drove and a scene of heart-aching beauty in the moonlight, down eighteen miles of low trestle causeways, flying above the water; then down into the sea like a depth charge and up onto the high, level bridges like an epiphany in a New Yorker story we went. And out through Norfolk and into the narrow, twisting roads along the North Carolina border, we were just wreathed in shit-eating grins all the way to Raleigh, where there’s a young lady named Karen I’m particularly fond of.

Now, joy that it was, the car still wasn’t running exactly right, especially when Julian was driving, which satisfied my prideful youth. Whenever we had to drive slowly, there was some misfiring and the little pair of catalytic-converter overheat lights would light, showing a plug or three to be fouled. There was a Ferrari dealership in Greensboro, so, the next morning, I put Karen into the Ferrari and talked Julian into following us in Karen’s old Pinto station wagon. I can’t help wondering about Julian. Had I been misreading the man for a number of years or was he completely transformed after one experience behind the wheel of a 308GTS? Because as soon as I got into the cockpit with this young lady, I naturally began showing off, playing Patti Smith and the Clash on the cassette deck and doing 80 and 90 in the Raleigh suburbs, forgetting that I had the map and the directions and Julian would perforce have to follow me. And once I got past Durham and out onto I-85, I put some real will into my do-fast foot. That Pinto had over 100,000 miles on it and a lot of girl-style maintenance, and I don’t think anyone had ever gone over 60 in it. But when I got out of the Ferrari at Foreign Cars Italia in Greensboro, there was Julian pulling right in behind me, the Pinto’s valve clatter and piston ring blowby only a little worse than before. I don’t know how he did it.

But I do know how they did it at Foreign Cars Italia. They did it with great courtesy and good humor. Stephan Barney, who runs the place, just stopped what they were doing, cleared out a bay, and put their top mechanic, Tom Jones, to work on the engine. Tom spent all afternoon on the 308’s innards, and his verdict was Christmas vacation at Ferrari North America. The car had only had about 6000 miles on it when we picked it up, and it was ready for its first big post-break-in tuneup. This was supposed to have happened back in Montvale, but maybe, between holiday havoc and various vacation schedules, it sort of got phoned in. Anyway, two of the carburetors were running a little lean and two were running a little rich, and, yes, I’d started it up all wrong and had myself to blame back on the Garden State Parkway. But Jones showed us one other problem we were having and why the car lost power when Julian drove. Under the driver’s seat there’s a cutoff switch that shuts the engine down after five seconds without weight on the seat cushion. This is in case you turn turtle and are lying on your head with gasoline running up your pants leg, so that the car won’t pull a Molotov mixed drink on you. Julian weighs about twenty pounds less than I do, and it seems that he just doesn’t produce enough downforce to keep this switch from un-switching. An admirable safety device, no doubt, but we just don’t eat as much pasta as the Italians do, so Tom hot-wired it for us. And at the end of the day, Mr. Barney gave us a bill for all of $66. Therefore, I must heartily recommend that you drive over to Foreign Cars Italia in Greensboro, North Carolina, when you buy your next Ferrari, even if you live in France.

Karen headed back to Raleigh in the poor Pinto. And Julian and I set out to try for the nighttime fast-driving-and-Scotch-drinking-with-a-large-dinner record time to Atlanta. The engine had a better pitch since Tom Jones had gotten through with it. The car was even faster, even smoother than before and absolutely bulletproof now. We would put nearly 3000 more miles on it, most of them at over a hundred miles an hour, and the solitary mechanical problem we would have between Greensboro and L.A. would be the electric antenna’s bezel vibrating itself off somewhere in east Texas, so that when I went to put the antenna up it would shoot six feet out of the right rear fender, trailing its line like a harpoon out into the middle of the LBJ Hilton parking lot.

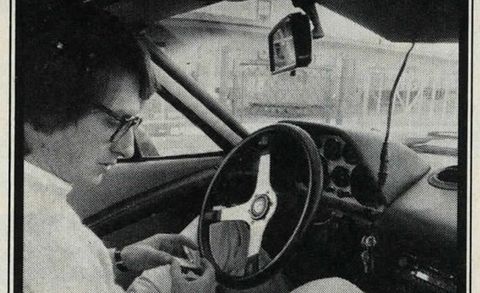

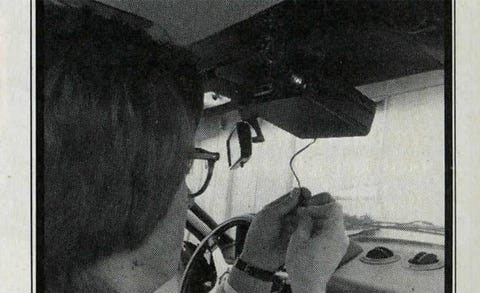

It was on our way to Atlanta that Julian and I began to feel really at home in the Ferrari, began to feel sharp with its stiff little clutch and slim shift gates, with the frightening immediacy of its steering straight from your left brain to the road, and began to feel comfortable half-recumbent in that future closet filled with levers and toggles, not a wasted square inch of anything, hardly room for the tapes and the cigarettes, with maps, flashlights, and sunglasses bulging out of the leather pockets in the doors, radar detector clipped on the right sun visor with its patch cord hanging down to the dash, everything faintly bathed in the businesslike night-bombing luminescence of the indicators, gauges, and dials. Felt we could stay in there for a whole Apollo mission if only we had relief tubes, screaming along in the night with a tape of Bruce Springsteen’s street-racing songs for a score in a car that had ceased now to look strange or exotic or even pretty or not because it just looked like the apotheosis of perfect speed from perfect function through perfection of design to the perfection of our mood out there in something that could outhandle anything it couldn’t outrun, and there wasn’t anything it couldn’t outrun.

When we got to Atlanta, the band in the hotel bar was the worst thing we’d ever heard. But it didn’t matter. Nothing could cloud our outlook. Brock Adams and Joe Califano could have sat down at our table. Ralph Nader himself would have been welcome, so infected were we with the spirit of vast superiority to the humdrum concerns of daily life that the Ferrari confers, or something like that. I mean this car does one thing. It makes you happy, really happy.

And the car did one more thing for me. It reaffirmed my belief in America. It may sound strange to say that a $45,000 Italian sports car reaffirmed my belief in America, but, as I said, it’s all part of Western civilization and here we were in America, the apogee of that fine trend in human affairs.

And, after all, what have we been getting civilized for, all these centuries? Why did we fight all those wars, conquer all those nations, take over all that Western Hemisphere? Why, for this! For this perfection of knowledge and craft. For this conquest of the physical elements. For this sense of mastery of man over nature. To be in control of our destinies—and there is no more profound feeling of control over one’s destiny that I have ever experienced than to drive a Ferrari down a public road at 130 miles an hour. Only God can make a tree, but only man can drive by one that fast. And if the lowly Italians, the lamest, silliest, least stable of our NATO allies, can build a machine like this, just think what it is that we can do. We can smash the atom. We can cure polio. We can fly to the moon if we like. There is nothing we can’t do. Maybe we don’t happen to build Ferraris, but that’s not because there’s anything wrong with America. We just haven’t turned the full light of our intelligence and ability in that direction. We were, you know, busy elsewhere. We may not have Ferraris, but just think what our Polaris-missile submarines are like. And, if it feels like this in a Ferrari at 130, my God, what can it possibly feel like at Mach 2.5 in an F-15? Ferrari 308s and F-15s—these are the conveyances of free men. What do the Bolshevik automatons know of destiny and its control? What have we to fear from the barbarous Red hordes?

Actually, at the time when this thought occurred to me we were out in West Texas, half a thousand miles from any population center or major military base, so Julian and I probably had nothing at all to fear from the barbarous Red hordes. The highway patrol, however, was another matter. You may wonder how we kept ourselves from being fined into starvation or, anyway, thrown into jail during this transmigration. The credit for that goes all to the Escort radar detector. The Escort is generally considered the best available radar detector, and it certainly never let us down. Not only did it have extraordinary range but it could detect the distant bounce of the instant-warmup-type K-band radar when it was being used against someone else up the road—thus giving us fair warning. After a couple of days we learned to read the machine so that we could tell even at what angle the radar gun was pointed and whether it was in a moving patrol car or a stationary one. The Escort could also detect radar coming up behind us. But we only know that from the cities because, out on the road, there was no one coming up behind us. In fact, our biggest legal danger lay not in getting apprehended by the police but in apprehending them, coming up over some rise at 110 or 120 and rocketing up the tailpipe of an unsuspecting smokey.

We spent a lot of time peering down the road trying to figure out what we were about to overtake, and every time we crossed a state line we had to spend about an hour figuring out what that state’s patrol cars looked like. If I were doing this again I’d take along a pair of light-intensifying binoculars.

But, as it was, we only got one ticket all week. It was on the last night, right after the New Year’s weekend, in jammed-solid, rush-hour-like traffic from Las Vegas to Los Angeles. We were in California, where the highway patrol doesn’t even have radar, and all we were trying to do was get around one carload of vacationers to get stuck behind the next when we were pulled over. Officer Huyenga (as best I can make out his signature on the ticket) was politeness itself and should be promoted to governor. “It’s a shame,” he said, “to have a car like this and only be able to go 55.” We suppressed a chuckle, and I believe he did, too, and so we got our only ticket—for going ten miles an hour over the limit.

From Atlanta to Dallas we’d stayed on the Interstates, but once past Fort Worth we took the empty, two-laned U.S. 180 across the astonishing West Texas landscape and then, in the twilight, through the big mesas that make up the southeast corner of New Mexico. There we got into our only other real race of the trip, with a pickup truck full of drunk bauxite miners or some such, and those boys could really drive a pickup truck. They held their own up through a hundred miles an hour on the curves and bends into Carlsbad, and then we left them and went back into Texas down switchbacks and hairpins skirting the edges of Guadalupe Peak.

This was where I first discovered why you wear driving gloves. I’d always thought they make you look like a golf pro, but somebody had given me a pair as a going-away present and I found that you wear them because of how much your palms sweat when you’re scared. But the Ferrari was just as solid at 90 and 100 in the mountains as it had been at 130 in the straights. Nothing that either of us ever did so much as made one tire blush with the thought of wavering from its appointed course. In fact, the only thing that made the mountains exciting was that, although the Ferrari wasn’t going to put us over the side, there was every chance that Julian or I might. But we didn’t, and we drove into El Paso for the evening.

No matter how many times you’ve seen it, it’s incredible the way the cities of the Southwest pop up from nowhere at night—vast, glowing fairylands. Although in this particular fairyland we took a wrong turn and wound up with an accidental ten-minute tour of Ciudad Juárez. The Ferrari startled the Mexican customs official into a ballet of Señor-you-may-pass-through-with-pleasure-with-honor-with-gratitude pantomimes. I’m sure it made his night. The Mexican customs official startled us, too, because that was when we discovered we were in Mexico; with horrible visions of Ferrari confiscations, I got turned around and headed back to America. The American customs officials were also extremely courteous. I guess they figured that whatever it was we were smuggling we’d already smuggled it and were happily living off the proceeds, so it was too late now. Juarez, incidentally, greatly testifies to the value of Western civilization by exhibiting no sign of it anywhere.

The next day we drove to Las Vegas. Oh, the pure joy of the thing—knowing that out there, down that road, there’s a fellow doing 65 or 70, a little nervous, watching for cops, maybe his wife’s telling him to slow down, and then screaming out of nowhere comes something not half his height, an eardrum-popping Doppler whizz just beneath the very bone point of his left elbow resting on the window frame. Whaizzat??!!! What was that??!! Passed you at your speed times two? We could see his bumper wiggle behind us as he’d give the wheel a startled jerk, and we’d be in the next county before that fellow’d regain his composure.

Julian hit the record high speed of our trip, 140, on I-10 going into Deming, New Mexico. And at Lordsburg we turned off onto U.S. 70 up into the mountains and Indian reservations east of Phoenix and from there across the desert all the way to Lake Mead. And we didn’t meet a single dislikable person. Not that day or any other, from the puzzled receptionist at Ferrari North America to Officer Huyenga of the California Highway Patrol. Fine, upstanding, friendly, outgoing Americans who wanted to know how fast it would go, every one. It was truly heartening. The nicest bunch of people you’d ever care to meet. It made me wish I didn’t belong to the Republican Party and the NRA just so I could go out and join both to defend it all.

And rolling through the desert thus, I worked myself into a great patriotic frenzy, which culminated on the parapets of Hoover Dam (even if that was kind of a socialistic project and built by the Roosevelt in the wheelchair and not by the good one who killed bears) with the Ferrari parked up atop that orgasmic arc of cement, doors flung open and Donna Summer’s “Bad Girls” blasting into the night above the rush of a man-crafted Niagara and the crackle and the hum of mighty dynamos. Uplifted, transported, ecstatic I was, as a black man in a big, solid Eldorado pulled up next to us and got out to shake our hands. “You passed me this morning down in New Mexico,” he said. “And that sure is a beautiful car. And you sure must have been moving because I’ve been going 90 on the turnpike all day and haven’t stopped for anything but gas and I just caught up with you now.” But we hadn’t been on the turnpike, we told him. We’d been all through the mountains and had stopped for lunch and had been caught in Phoenix traffic half the afternoon. “Goddamn!” he said, “that’s beautiful!” Now where on the face of God’s green earth are you going to find a country with people like that in it? Answer me that and tell me any place but here and I’ll strangle you for a Communist spy.

That was New Year’s Eve, and we celebrated that night in the MGM Grand. I’m sorry to say that the Ferrari does not confer great good fortune at the blackjack table. But we were paid a fine compliment the next day at Caesars Palace. Instead of making us wait for valet parking, the lot jockey rushed up to us where we were fifth or sixth in line. “No receipt necessary for you, sir,” he said, and swept the car around in a tight U-turn and parked it right in front.

And that evening we headed up the Barstow incline to Los Angeles and got our ticket and I dropped Julian off so he could return to the staid world of business acumen, if he can. I kept the Ferrari for as long as I could the next day, roving around Beverly Hills and driving up and down Mulholland Drive, but it had to be delivered to Ferrari’s West Coast headquarters in Compton by five o’clock. It was a terrible thing to give it back, but I headed down the Harbor Freeway feeling every bit as good as I had for every moment since we first hit a hundred back in Delaware. It was a glow that wouldn’t fade. And I still felt good when I flipped the keys onto the receptionist’s desk. And I still felt good when I hopped into the limousine I’d thoughtfully charged to Car and Driver to ease the pain of transition. And, in fact, I still feel good today.

But the story ends on a sad note. The movie that this incredible car traveled all that way to be in will be called Don’t Eat the Snow from Hawaii, so maybe Western civilization hasn’t quite been perfected yet.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io