Imagine stepping off a plane in a foreign country. Emerging from the automatic sliding doors, a lot looks the same, but there’s always something reminding you that you’re not at home. Buses and taxis swarm to pick up new arrivals, but the signs are in a language you cannot read, and you pay the fare using a bill decorated with a historical figure who never appeared in your schoolbooks. Maybe you stop in a McDonald’s, expecting to get a taste of home, only to find dishes like the taro pie that replaces apple pie on the Mickey D’s menu in China.

Driving a 1915 Ford Model T elicits similarly conflicting feelings of familiarity and foreignness. The Model T is a car, with wheels and tires, pedals and levers, and a circular steering wheel. But it’s not a car as we know it today. Three pedals protrude from the floor, but none of them control the throttle, and the one you would expect to be the gas pedal instead stops the car. Seatbelts and airbags are nonexistent, of course, but even windows were a luxury that many Model Ts did without. And unlike the computer-controlled machines of today, in the Model T, the driver had to dial in the fuel mixture and spark timing on their own, requiring a close and attentive relationship with the vehicular beast.

Despite going out of production nearly a century ago, the Model T still ranks among the top ten bestselling cars of all time. Across a 19-year period, Ford built more than 15 million Model Ts thanks to Ford’s pioneering transition from traditional hand-building to the assembly line. That made the Model T one of the world’s first mass-produced cars and certainly the most successful of its era, and with such a vast number built, there remains a healthy enthusiasm for keeping Tin Lizzies on the road. So when we were offered the chance to drive a Model T, we leaped at the opportunity to learn how to operate the car that put America on wheels and has captivated millions of people for decades.

Learning the Ropes

Clamber into the Model T’s driver’s seat—which is really more like a sofa jammed into a metal bathtub—and you are met by a dizzying array of controls. First off, none of the three pedals acts as the accelerator. Instead, throttle inputs are controlled by a stalk mounted behind the steering wheel on the right, where you might find the windshield-wiper activator on a modern car.

The stalk on the left side of the steering wheel is the spark advance, which controls the spark timing. When starting the Model T, the lever should be in the highest position to fully retard the timing, and once the engine is running the timing is advanced to smooth out the idle.

The brakes, meanwhile, are modulated by the pedal on the far right side. While it’s handily labeled with a B, reprogramming our brain to remember that the right pedal slows the Model T instead of propelling it forward was one of the most challenging issues to master. Unlike today’s cars, the Model T’s brake slows the transmission, although this example had auxiliary disc brakes fitted at the rear, a common upgrade since the original braking system was particularly weak.

The leftmost pedal is usually described as the clutch, but it doesn’t operate like the clutch on modern manual-transmission cars. Instead of a range of motion that allows for precise modulation, the Model T’s clutch has three distinct positions and acts more as a gear selector. The middle, halfway-down position puts the Model T into neutral, while pressing the pedal to the floor puts the car into the “low gear.” Getting moving and into first gear requires slowly pressing the clutch down while easing onto the throttle—using the steering-wheel-mounted stalk, remember—and off the brake. Once underway, letting the pedal all the way out puts the Model T into the high gear necessary for normal cruising speeds. Finally, the middle pedal is used to activate the reverse gear and can, in a pinch, aid the brakes in slowing the car.

But there’s still more to wrap your head around. To the left of the driver is a lever sprouting from the wooden floor that serves two functions. Pulled all the way toward the driver, it serves as the parking brake. Moving the lever forward part way puts the Model T in neutral, while pushing the lever all the way forward puts the car into high gear, in turn popping the clutch pedal all the way up.

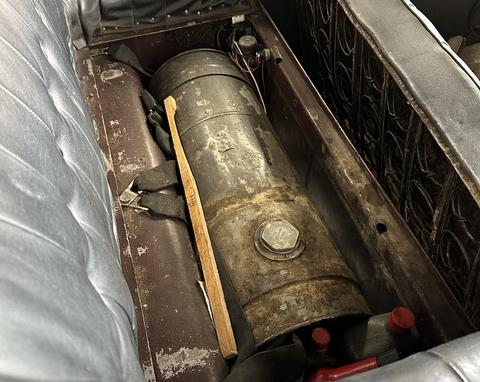

The only other features in the interior are a choke, used to prime the carburetor with fuel when starting the engine, and a coil box, which holds the battery. The Model T only gained an electric starter in 1919, but this 1915 example has one retrofitted. Without it, the car would need to be cranked by hand to start, and if done improperly, the engine can violently misfire, potentially breaking your arm or wrist. The fuel tank resides under the couch cushion seat, and the driver’s-side door is actually fake, requiring you to slide across the seat when getting in and out from the passenger’s side.

The car we drove was also fitted with a Ruckstell two-speed rear axle, one of the few aftermarket accessories that were approved by Ford. The extra gearbox essentially adds an even lower gear—which in modern contexts can be useful when slowly crawling forward during parades—and a high gear that sits between the standard Ford low and high gears and allows you to scale hills that are too steep for the T’s high gear while going faster than in its low range.

Behind the Wheel

Remember that first stress-ridden drive as a 15-year-old when every input of the throttle or steering took serious consideration? Driving the Model T was a little like that, although instead of acquiring new skills against a blank canvas, as we did as teenagers, we now had to expel every ounce of instinct we’d gained in our years of driving. Need to panic stop? Instinct tells us to stab the brake and clutch pedals, but in the Model T, pushing the clutch to its middle position puts it in neutral, while pinning it to the floor would keep you in gear. Each interaction between you and the car takes extreme concentration and prevents you from admiring the scenery for too long.

The Model T’s 2.9-liter inline-four emits a lively rumble, the whole car shaking as you gradually build speed. The combination of engine and wind noise requires you to shout if you want to converse with your passengers. Like many cars of the era, the Model T is tall and upright, with a seating position far above than that of many modern vehicles. This heightens the sense of speed and makes turning and braking a nerve-wracking affair since it feels like you might tip over if you do anything too suddenly. The steering is incredibly heavy—you have to put your whole body into it to execute a U-turn—and braking requires advanced planning and a muscular right leg. The Model T’s ride is not nearly as composed as any car on sale today, of course, and was developed at a time when paved roads were few and far between. Maybe that’s why it was surprisingly smooth on our drive across a grassy field.

It’s unlikely we exceeded much past 20 mph, though without a speedometer we are left to guess. Even so, once at cruising speed in the Model T, objects that our brains would normally gloss over seemed to loom larger out in front of us.

Between the stress of actively learning a new skill set and the fear of breaking someone else’s car while they sit beside you on the passenger seat, moseying along at cruising speed in a cockpit sans windows with walls that barely rise above your waist while a 25-degree November wind blows through is enough to make even 5 mph feel like 50. Our hats are off to the drivers of yesteryear—they did not have it so easy.

This content is imported from Tiktok. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.