When it comes to electric vehicles, range is the all-important stat. Whether or not you make it to the next public charging spot, are able to complete your daily commute, or are instead stranded on the side of the road depends on it.

Range is so heavily scrutinized because EVs can travel on average barely half the distance of gas-powered vehicles before they require a “fill-up,” and because gas pumps are far more ubiquitous than fast chargers. Most EV range discussions are centered around the EPA combined range, as that’s the one that’s published prominently on the window sticker. For the 2022 model year, 61 EVs have EPA ratings (this includes multiple variants of the same vehicle), and the combined-range figures span from 100 miles for the Mazda MX-30 to 520 miles for the Lucid Air Dream Edition Range.

There’s More Than One EPA Range Figure

As with gas vehicles’ EPA fuel-economy estimates, there are also separate ratings for EVs’ city and highway range, too. Unlike gas-powered vehicles, whose highway efficiency almost always exceeds the city figure, all EVs except Audi’s e-tron models and the Porsche Taycan have higher city range ratings than highway. Part of electric vehicles’ magic in low- and variable-speed scenarios is their ability to recapture energy when decelerating by slowing the vehicle using the electric motor (or motors) rather than the traditional brakes.

Another way EVs are different is that range and efficiency aren’t directly related. That’s because of charging losses; roughly 85 to 90 percent of the total energy that comes from the wall makes it into the battery pack. That’s why there are two terms used: efficiency, which can be expressed in MPGe, includes charging losses, while consumption, the energy use while driving, doesn’t include them.

Our EV range test is done at a steady 75 mph, because highway driving is where range matters most. If you’re looking to cover 500 or 1000 miles in a day, it necessarily has to be done at high speeds. There are just not enough hours in the day to do otherwise. Even the shortest-range EV can manage more than seven hours of slogging through city traffic at an average speed of, say, 15 mph. Also, unlike a gas-powered vehicle, an EV’s consumption increases dramatically as speeds rise. Of course, as with all cars, aerodynamic drag inflates with the square of speed, but EVs are particularly affected as all but the Audi e-tron GT and Porsche Taycan lack multiple gears. So, a higher vehicle speed means the electric motor is spinning at a faster and less efficient point.

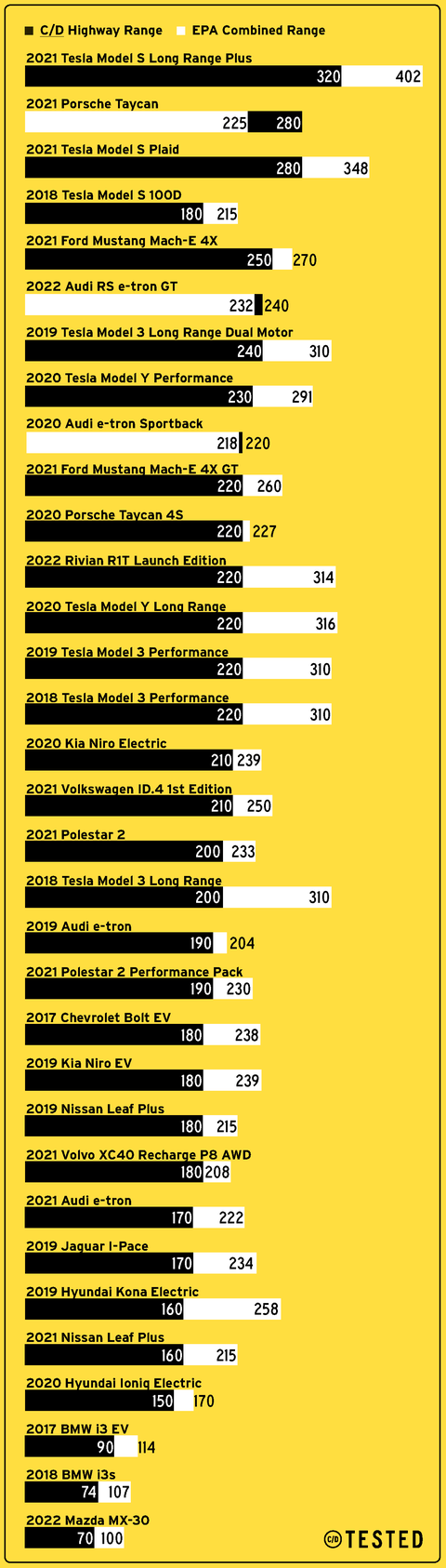

Electric Vehicles Rarely Match or Exceed Their Range Rating in Our 75-MPH Highway Test

Unlike gas- or diesel-powered vehicles, which regularly beat their EPA ratings in our highway testing, only three of the 33 EVs that we’ve run range tests on to date have exceeded their EPA highway and combined figures. Currently, that’s the Audi e-tron Sportback, Audi RS e-tron GT, and base-model Porsche Taycan. We use the combined figure as the primary point of comparison because the city and highway range figures for EVs are much closer than for gas-powered vehicles, and we want to avoid confusion by using something other than that most familiar figure.

The base model Taycan with the optional 83.7-kWh Performance Battery Plus exceeded its 225-mile EPA rating by 55 miles or 24 percent, traveling 280 miles in our 75-mph highway range test. The Audi RS e-tron GT made it 240 miles, eight miles over its EPA rating, and the Audi e-tron Sportback was only two miles ahead of its EPA rating at 220 miles.

We don’t (yet) control the weather, so the worst-performing examples, including a 2018 Model 3 that only managed 65 percent of its range rating, took place with outside temperatures hovering around freezing. Which brings up another way EVs are different: cold weather affects range dramatically. One of the many reasons for that is that using the heater to warm the cabin—particularly on EVs that have resistive heaters—sucks a lot of juice. In a test with our long-term Model 3 we found that using the heat can increase consumption by as much as 35 percent and kill 60 miles of range, a significant chunk of the Model 3’s 310-mile EPA rating.

Also, you should consider our range figures the absolute maximum possible and, as with our zero-to-60-mph times, it will be difficult to achieve them with any regularity. That’s because it involves charging the battery all the way to 100 percent, which is not the EV norm. Topping off the last 10–15 percent is when the rate of charging slows considerably, and it also leads to increased degradation in battery capacity over time. For example, Tesla recommends limiting charging to 90 percent for daily use. Even on long-distance trips, the stops are determined more by the charging infrastructure than anything else, and the most expeditious method is to top up the battery just far enough—to maybe 80 or 90 percent, keeping it in the speedy part of the charge-rate curve—to get to the next charger.

Range is critical; range is complicated. And if you want to drive an EV long distances and you live in a place where it gets cold, plan on a large buffer between the EPA combined rating and what you actually will be able to use.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io