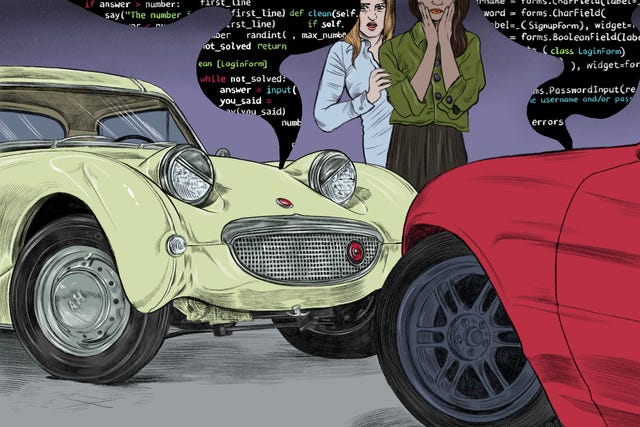

Illustration by Dilek BaykaraCar and Driver

From the September 2022 issue of Car and Driver.

Early in June, Blake Lemoine, an engineer at Google working on artificial intelligence, made headlines for claiming that the company’s Language Model for Dialogue Applications (LaMDA) chat program is self-aware. Lemoine shared transcripts of his conversation with LaMDA that he says prove it has a soul and should be treated as a co-worker rather than a tool. Fellow engineers were unconvinced, as am I. I read the transcripts; the AI talks like an annoying stoner at a college party, and I’m positive those guys lacked any self-awareness. All the same, Lemoine’s interpretation is understandable. If something is talking about its hopes and dreams, then to say it doesn’t have any seems heartless.

At the moment, our cars don’t care whether you’re nice to them. Even if it feels wrong to leave them dirty, allow them to get door dings, or run them on 87 octane, no emotional toll is taken. You may pay more to a mechanic, but not to a therapist. The alerts from Honda Sensing and Hyundai/Kia products about the car ahead beginning to move and the commands from the navigation system in a Mercedes as you miss three turns in a row aren’t signs that the vehicle is getting huffy. Any sense that there’s an increased urgency to the flashing warnings or a change of tone is pure imagination on the driver’s part. Ascribing emotions to our cars is easy, with their quadruped-like proportions, steady companionship, and eager-eyed faces. But they don’t have feelings—not even the cute ones like Austin-Healey Sprites.

How to Motor with Manners

What will happen when they do? Will a car that’s low on fuel declare it’s too hungry to go on, even when you’re late for class and there’s enough to get there on fumes? What happens if your car falls in love with the neighbor’s BMW or, worse, starts a feud with the other neighbor’s Ford? Can you end up with a scaredy-car, one that won’t go into bad areas or out in the wilderness after dark? If so, can you force it to go? Can one be cruel to a car?

“You’re taking it all the way to the end,” says Mois Navon, a technology-ethics lecturer at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Beersheba, Israel. Navon points out that attempts at creating consciousness in AI are decades deep, and despite Lemoine’s thoughts and my flights of fancy, we’re nowhere near computers with real feelings. “A car doesn’t demand our mercy if it can’t feel pain and pleasure,” he says. Ethically, then, we needn’t worry about a car’s feelings, but Navon says our behavior toward anthropomorphic objects can reflect later in our behavior toward living creatures. “A friend of mine just bought an Alexa,” he says. “He asked me if he should say ‘please’ to it. I said, ‘Yeah, because it’s about you, not the machine, the practice of asking like a decent person.’ “

Paul Leonardi disagrees—not with the idea of behaving like a decent person, but with the idea of conversing with our vehicles as if they were sentient. Leonardi is co-author of The Digital Mindset, a guide to understanding AI’s role in business and tech. He believes that treating a machine like a person creates unrealistic expectations of what it can do. Leonardi worries that if we talk to a car like it’s K.I.T.T. from Knight Rider, then we’ll expect it to be able to solve problems the way K.I.T.T. did for Michael. “Currently, the AI is not sophisticated enough that you could say ‘What do I do?’ and it could suggest activating the turbo boost,” Leonardi says.

Understanding my need to have everything reduced to TV from the ’80s, he suggests that instead we practice speaking to our AI like Picard from Star Trek, with “clear, explicit instructions.” Got it. “Audi, tea, Earl Grey, hot.” And just in case Lemoine is right: “Please.”