- Today you can listen to whatever you want on Apple Music or Spotify, but back in the 1960s, your Christmas music was on the radio or on vinyl.

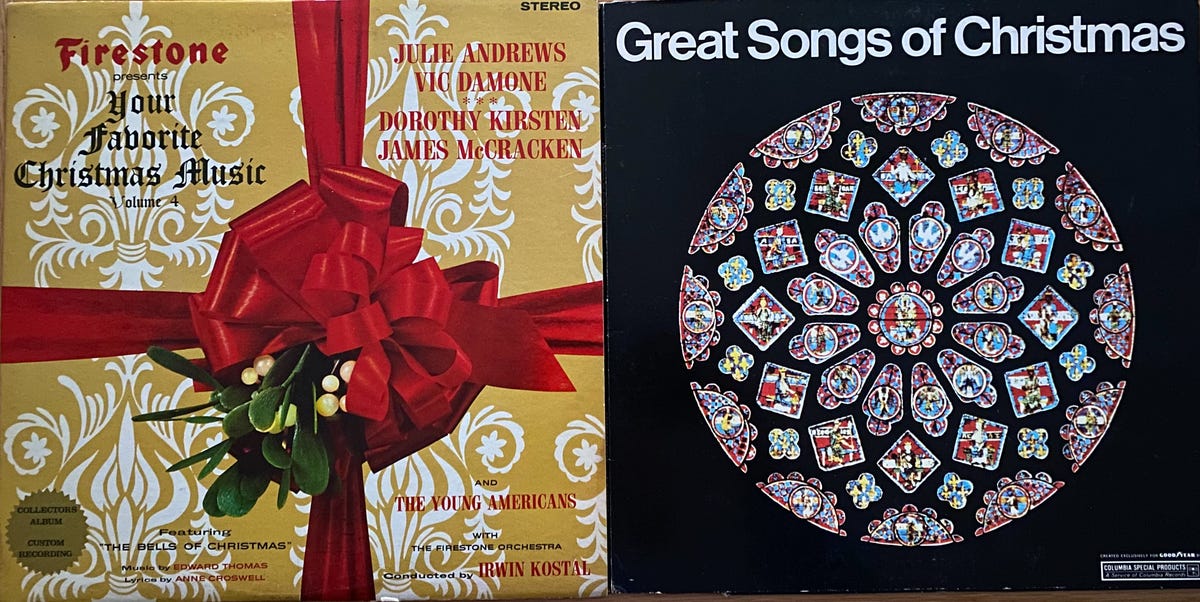

- It seems unlikely today, but Goodyear and Firestone sold holiday music alongside tires during holiday seasons of the 1960s and early 1970s.

- As an Ohio-based LP-to-MP3 conversion company is still doing a booming business with these classic discs, although the era of getting them at tire stores is long gone.

From Spotify playlists to radio stations starting holiday tunes on Black Friday, it’s nearly impossible to avoid the sounds of the Christmas spirit. But back in the 1960s, if you wanted a compilation of holiday tunes, chances are you picked it up at the same place you’d get a new set of whitewalls. From 1961 to the mid-’70s, well before Mariah Carey’s monopoly on the holiday spirit, tire manufacturers such as Goodyear and Firestone offered Christmas records in their stores for about $1 (the equivalent of approximately $9.40 today).

Stanley Arnold was the man responsible for the unlikely, yet successful, pairing of rubber and Rudolph. Arnold worked at an advertising agency before striking out on his own and convincing executives at Goodyear to lure customers into its stores with something that today anybody with a smartphone can access: a who’s who of classic Christmas covers. Arnold’s idea helped Goodyear sell more than 15 million records—not to mention millions in tire and accessory sales—over 17 years.

The albums even remain popular today. “They are still our bestsellers, particularly the Goodyear and Firestone albums,” said David Feinauer, co-owner of

Christmas LPs to CD, a Cincinnati, Ohio, company that converts vinyl into downloadable MP3s and CDs. “For Goodyear, the 1965 and ’66 [albums] are the two most popular; the Firestones have a more even demand.”

A Lucky Strike

But how did Arnold associate Christmas music with tire companies? The idea, as he wrote his 1968 book Tale of the Blue Horse and Other Million Dollar Adventures, started after a meeting at Lucky Strike’s headquarters in Durham, North Carolina. Arnold and others were invited to pitch ideas that would help boost cigarette sales.

“All the way back to the office I kept humming the tune of the Lucky Strike television commercial that had been played at the meeting,” Arnold wrote. “I decided that music would reverse the sales decline of Lucky Strike.”

Arnold’s idea was to offer a collection of music, pulled from Columbia Records, to those who mailed in $1 and proof of purchase of Lucky Strikes. It wasn’t long until sales climbed. The plan proved successful, and Arnold set out to repeat it with another billion-dollar industry: tires.

A Goodyear for Christmas Music

With the runup to Christmas being a big season for tire sales, Arnold bet that music could draw people into Goodyear’s then 60,000 retail outlets. Arnold pitched the idea that buyers would be interested in a Christmas music album.

One of the ways he made it easy for a tire company to agree to sell records was by proving it wouldn’t cost them anything. Arnold worked with Columbia Records, which agreed to put together a collection of its best recording artists, which it would offer to Goodyear as an exclusive for only $1 per record. As long as Goodyear sold the records for the same amount, the tire company wouldn’t pay a penny for the albums. Even if no one bought a tire, chances were that these companies wouldn’t lose money from this scheme.

For the inaugural Great Songs of Christmas, Arnold amassed a collection of timeless songs that included the Mormon Tabernacle Choir singing “Silent Night” and the Leonard Bernstein–led New York Philharmonic’s version of “Unto Us a Child Is Born,” as well as classics such as “The First Noel,” “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” and “Deck the Halls.” Despite Arnold’s suggestion to order 3 million copies, Goodyear countered with 90,000 records. Arnold worked to get the order up to 900,000.

Christmas by the Fire(stone)

It was around this time Arnold heard that Firestone was working with RCA Records on a Christmas album. Of the conspicuous timing, Arnold wrote: “These coincidences are common in the world of ideas, but the deciding factors are the relative quality of the ideas and the determination with which management supports them.”

By December 1, 1961, after only a few weeks of sales, Goodyear stopped promoting the Christmas album—the tire giant had sold every record it ordered. When Goodyear’s second Christmas album came out in 1962, it sold every one of the 1.5 million copies it ordered. This trend continued, too. By the time Goodyear’s sixth Christmas album came out, the tire company had upped its order count to 4 million records. Once again, they sold out. Eventually, distribution for the Goodyear Christmas compilations switched from Columbia Records to RCA Records. As a result, a different set of artists appeared on these albums, including Julie Andrews and Ella Fitzgerald.

Firestone, meanwhile, released a total of seven Christmas records starting in 1962 and ending in the 1970s. Whereas Goodyear’s records often featured images of the artists, Firestone’s featured a bow. Feinauer categorized the Goodyear albums as having more of a pop twist with songs such as “Jingle Bells.” The Firestone collections, meanwhile, skewed a bit more traditional, as shown by the records’ more modest branding.

By the mid-’60s, the trend of tire companies selling Christmas music was firmly established, with other tire manufacturers, including BFGoodrich, joining in. Other stores, such as JCPenney and Sears, soon offered Christmas records of their own. With this increased competition, sales of such albums from tire companies began to wane. Before long, the era of tire manufacturers selling Christmas records came to a close.

This content is imported from OpenWeb. You may be able to find the same content in another format, or you may be able to find more information, at their web site.