My youngest child, Milo, and I have something of a tradition, rendezvousing in Florida during school spring break each year with a onetime denizen of the Sunshine State—my old college buddy Richard Hart, lifelong newspaperman turned well-read layabout and amateur historian—to hit baseball’s preseason Grapefruit League, also known as Spring Training. This year, after a long COVID layoff, it was back on.

Landing in Tampa, we scooped up a

Mercedes-AMG E53 cabriolet, finished in a shade of very dark green, very subtle, very handsome. It’s Florida, after all. Unless you’re boating, you don’t go anywhere in 99.8 percent of this state without your car. And for this frostbitten Northerner, the opportunity to let the sun shine in was too great to pass up.

Our traditional plan for a leisurely six days in the general area watching the Kitman clan’s first love, the Pittsburgh Pirates, down in Bradenton had, however, already been upended. A week before our departure Milo had pointed out that we might still buy tickets for the World Baseball Classic—not the all-American one I’d been following since childhood but a true World Series, in the sense that, like soccer’s World Cup, the quadrennial WBC actually features teams from around the world.

When we bought our tickets to Sunday night’s game, we had no idea what countries’ squads we’d be seeing, and we had to act fast. But by the morning we touched down in west central Florida, a long southerly ride to Miami in the suitably internationalist Benzer promised to deliver us to a truly historic matchup: the United States versus Cuba. We were fortunate to spend those five hours behind the wheel of the E53, a Mercedes-AMG that was launched in 2018 and facelifted in 2020. Its turbocharged 429-hp 3.0-liter straight-six, with a standard electrically driven supercharger, reacquainted us with a new type of more refined, less raucous AMG offering. Unfortunately, with the weather being unseasonably cold and with the forecast threatening rain, top-down motoring was not yet a serious option. Béisbol was.

International Intrigue on the Field

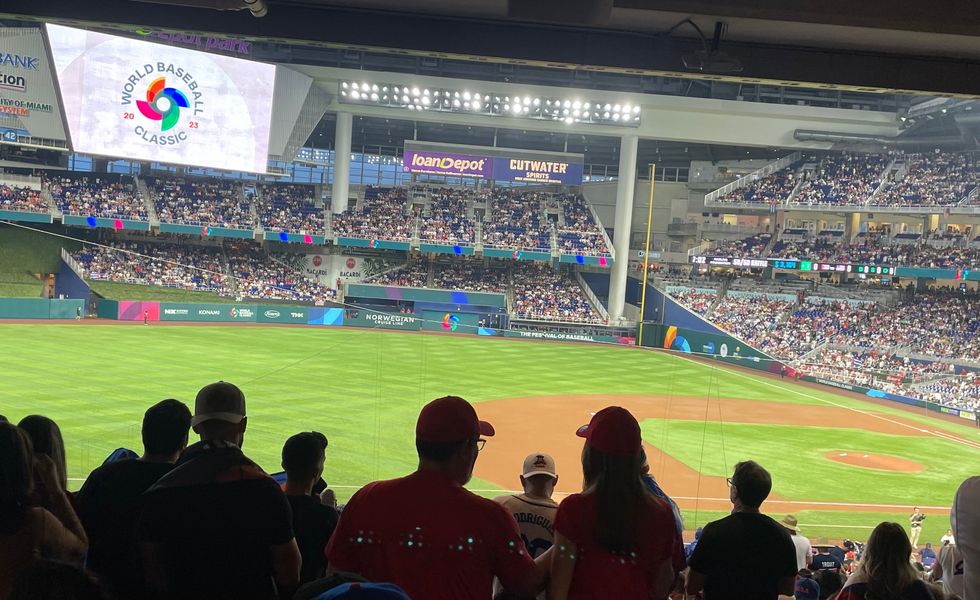

Cuba’s baseball fandom and the percentage by volume of its baseball-playing citizenry—versus other WBC entrants, say Great Britain—are legendary, for starters. Miami’s Cuban population is America’s largest and, adding to the monumental nature of the event, it was reportedly the Cuban national team’s first appearance in Miami since the Castro-led Cuban revolution of 1959. Sure, we’d seen Cuban refugees and asylum seekers playing in the major leagues before. But this time around, several defectors now playing in the majors were allowed to suit up with the Cuban national team. So right off the bat the feeling was electric, the park (its roof closed for predicted rain) was jammed to the rafters, 36,058 voices raised and reverberating, flags waving, everyone packed in, like loud-mouthed sardines in a can.

The name of the Florida Marlins Loan Depot Park tells you just about all you need to know: it’s a low-rent dome built with borrowed money and possessed of no special charm (even if the prices at the concession stands would suggest otherwise), with an unusual number of empty seats the rule at most regular-season games, no matter what kind of year the home team is having. But on this night, it was heaving, louder than any game I’ve ever attended. Especially when the Cuban team loaded the bases against the USA starter, Adam Wainwright, in the top of the first, with no outs.

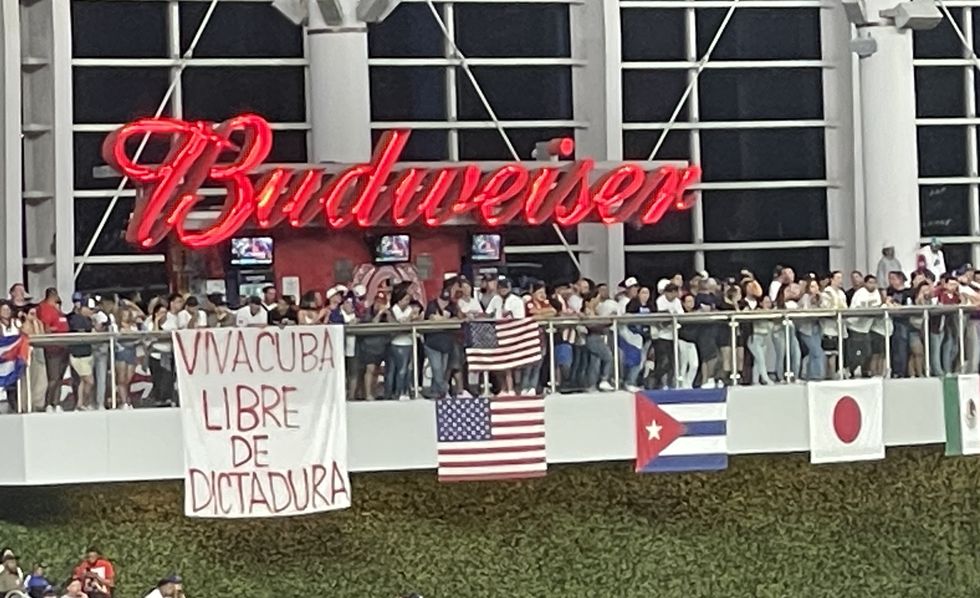

Vociferous chanting (mostly in Spanish), banners unfurled, it seemed like the pro-Cuban contingent had enough energy to blow the roof right off the joint. But then the wily and venerable Wainwright managed to shut the door, reaching deep into his bag of tricks to allow only a single run to score. Whereupon, in the bottom of the first, the American giants Mike Trout and Paul Goldschmidt doubled and homered, respectively, and, like a lightbulb blowing out, the boisterous enthusiasm subsided in a Miami nanosecond, with only the occasional flicker of Team Cuba cheering left.

What seemed like the beginning of a headline-grabbing upset would turn into a lopsided 14–2 victory for the USA. Yet, it bears mention, despite their overwhelming devotion to the Cuban team, these were South Florida Cubans and many seemed happy enough to cheer on the American squad, if not quite so loudly. As a 20-something young woman totally made up with a crop top and jeans, sitting next to her father in his button-down shirt explained. “We have a bet. If the U.S. wins he pays me $100 dollars, and if Cuba wins, I pay him $50.” She said Cuba is really run down but its beaches are great. “Have you been there?” she was asked. “Of course, seven times.”

Despite lots of chanting and sign waving, calls for the liberation of Cuba and the reinstallation of Donald Trump, including a fan running on the field unfurling a banner with an indiscernible message while the crowd bellowed “Libertad!” (Freedom!), a peaceful calm returned even as the history being played out before us failed to include a triumph for the Cuban squad.

Fans of Team USA got their comeuppance quickly enough the following night in a heart-wrenching 3-2 defeat at the hands of Team Japan and their star, Shohei “Shotime” Ohtani, a California Angel in between WBCs, the world’s highest-paid player and arguably its best. On a brighter note, the series finale boasted the largest U.S. television audience of any WBC game ever (6.5 million viewers, up 69 percent from the last WBC in 2017), while 42.4 percent of all Japan households—more than 50 million people—watched the game on television, at 8 a.m. local time no less, throwing the whole idea of a connected world into a new and exciting light. The USA may have lost the series, but America’s Major League Baseball, the American professional sports organization which runs the WBC, won big time. We’re expecting even better things for 2026.

But Back to Cars

Speaking of better things, the E53 cabriolet didn’t take long to grow on us, especially those in its comfortable front seats (less so in back for 5’11” and rising Milo) and more particularly the driver. The E53’s character is not that of the fire-breathing rumbler, like some AMG offerings, but it’s no slouch, a taut and reassuringly solid express carriage perfect for traveling great distances in comfort, as at home on the back roads that traverse the more interesting parts of Florida as it is on the vast interstates and flyovers that in the last century captured the imagination of the state’s developers as thoroughly as the railroads once had.

The inexorable taming of Florida’s beautiful but forbidding landscape and the state of the state today are at once monuments to and indictments of successive frenetic waves of development of a wild land courtesy of an uniquely Floridian combination of wild-eyed dreamers, shameless grifters and organized capital, going back centuries.

Taking the Top Down in Old Florida

Headed back up to Gasparilla Island, where we’d spend a couple of nights between ballgames, the E53’s droptop facility proved the perfect complement to the improved weather and back-road forays through old Florida, highlighting its powerful dual character. Like a switch hitter who can tee off from both sides of the plate, the air-suspended, AMG-kissed droptop was equally adept at high-speed highway cruising and carving up winding two-lanes, the best ones lined with old shacks, cypress and majestic banyan trees, which drop roots down to the ground from their branches. Its acceleration is vivid (the coupe posted 4.1 seconds to 60 mph in our testing). Its 384 pound-feet of torque is plentiful, steering is well weighted with handling aided by the E53’s rigid monocoque, and its overdriven nine-speed paddle-shifted automatic makes finding the right gear for the moment as easy as dispatching an infield pop-up.

Ever the historian, Hart, a New Orleanian by birth, brought along for our edification and amusement a well-thumbed copy of the WPA Guide to Florida, one of many such efforts published in the 1930s and assembled during the Great Depression by the Federal Writers Project under the auspices of the Roosevelt administration’s Works Progress Administration. Accompanying us through the many counties, it was largely useless in terms of charting modern interstates or fast-food locations, but for background in a state so rich in history and scoundrels, it proved worthwhile, a pleasure for any traveler who cares to know what might have been before the KFC and CVS opened up.

For instance, on the subject of the pirate José Gaspar, Gasparilla Island’s namesake (Gasparilla meaning “little Gaspar”), we learn: “A Spaniard who had stood in high favor at court until he stole a ship of the Spanish Navy, he gathered a band of cutthroats and established a base on Gasparilla Island . . . described as a man of polished manners and faultless attire, and well read in the classics. He was known to offer places in his band to captives who preferred piracy to death. Victims were not killed by walking the plank, but were shot and tossed overboard.”

Such a humanitarian. After a remarkable 40-year run as Florida buccaneers, though, in 1822, Team Gaspar and one of its piratical corvettes “gave chase to what appeared to be a large British merchantman; upon being overtaken the vessel lowered the English flag, ran up the Stars and Stripes, and uncovered a masked battery. With his ship riddled, Gasparilla wrapped an anchor chain about his waist and leaped into the sea.”

How to Know You’re a Diehard Fan

Speaking of pirates, history is great, but there remained the baseball team from Pittsburgh to consider. They’d endured an abysmal spring training—that is, if you consider wins and losses any indication of a team’s success. The diehard among us, such as son Milo, readily distinguished between the pre-season roster tinkering and the stress testing that occurs before the games get meaningful when showtime begins, which is to say starting this week, when the 2023 baseball season officially opened. Treated to a run of games in which the Pirates won two, lost one, and tied one, we considered ourselves lucky, hopeful we’d witnessed in person a step in the right direction.

Passing through cities and villages that still retained vestiges of the fishing and agricultural centers they once were, it’s hard not to compare them to the all-tourism-all-the time landscape, interspersed with rows of stucco and cinderblock one-story homes on crumbling streets nestled amid semi-tropical scrub oaks and palmettos.

Florida is very rich and Florida is very poor. Our E53, at approximately $92,000, made it hard for us to complain when we went looking one day for an off-site parking space. On a run-down Bradenton street near Lecom Park (the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine of Erie, PA, currently sponsors the park, the Grapefruit League’s oldest—erected in 1923—for reasons I still can’t fathom) where a toothless local offers us a spot for $20. The going rate, we’d later discover, is $10 or less, but after negotiating him down to $15, we acquiesced. Such is the price of apparent wealth.

Rolling into Tampa equipped with three freshly minted cases of sunburn, we enjoyed a wonderful three-night stay in the Gulf metropolis’s Ybor City district. While much of the state appears captivated by clamping down on the LGTBQ community, Ybor was busy preparing to celebrate its annual Pride Day with color and panache. The district’s history is once again fascinating, as the WPA Guide highlights. Following an open revolution in Havana in 1868, “many cigar makers migrated to Key West, where established factories offered employment.” But fire swept through Key West in 1886, leading many to move to a district east of Tampa, which they named Ybor City after one of their leaders, Vicente Martinez Ybor. Here the cigar makers toiled, rolling coronas, royals, perfectos, and panatelas by hand.

On our final full day in Florida, we drove alongside legendary Florida developer Henry Plant’s railroad line through scrub and car lots and roadside stands selling strawberry shortcake and past giant warehouse complexes, some empty, some not, on the road from Tampa to Plant City to Lakeland to Auburndale. A route that’s in the 1930s WPA Guide, it briefly runs alongside the inarguably miserable I-4 superhighway, which largely replaced it. But the past still lingers. Lunch at Peeble’s BBQ, a screened-in shack in Auburndale, recalls an earlier time.

Anyway, not all development is bad. Witness the E53, as sophisticated and cheerful an internal-combustion machine as you may ever need. Then again, not all development is good. Consider all the Florida citrus groves plowed under to make room for housing developments and, more recently, the arrival of a greening disease, Huanglongbin, with 80 percent of the Florida citrus industry’s trees afflicted and no cure yet found. Or the Red Tide, the algal bloom which saw all the restaurants we’d visit along the state’s Gulf shores prevented from selling from its once bountiful oyster beds, forced to rely instead on imported shellfish from Louisiana, Massachusetts, and other distant locales.

One thinks, too, of the immense new Red Sox complex we’d visited earlier in the week in Fort Myers, with its six fields and a fieldhouse. Compare that to the old, 1960s Chain of Lakes Stadium in Winter Haven in which the Sox once played each spring, an intimate 6000-seat park nestled between two lakes, where the great New Yorker baseball writer Roger Angell would recount in fine prose sitting back and watching an osprey flying in circles above its nest on the light posts in left field. Florida’s frantic development trend obviously isn’t a new phenomenon. But it’s the direction that the state keeps going, relentlessly looking to make a buck, now as always.

But for now, at least, we can still say, Play ball.

Contributing Editor

Jamie Kitman is a lawyer, rock band manager (They Might Be Giants, Violent Femmes, Meat Puppets, OK Go, Pere Ubu, among his clients past and present), and veteran automotive journalist whose work has appeared in publications including _Automobile Magazine, Road & Track, Autoweek, Jalopnik, New York Times, Washington Post, Politico, The Nation, Harpers, and Vanity Fair as well as England’s Car, Top Gear, Guardian, Private Eye, and The Road Rat. Winner of a National Magazine Award and the IRE Medal for Investigative Magazine Journalism for his reporting on the history of leaded gasoline, in his copious spare time he runs a picture-car company, Octane Film Cars, which has supplied cars to TV shows including The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, The Americans, Halston, and The Deuce and movies including Respect and The Post. A judge on the concours circuit, he has his own collection with a “friend of the friendless” theme that includes less-than-concours examples of the Mk 1 Lotus-Ford Cortina, Hillman Imp, and Lancia Fulvia, as well as more Peugeots than he is willing to publicly disclose.