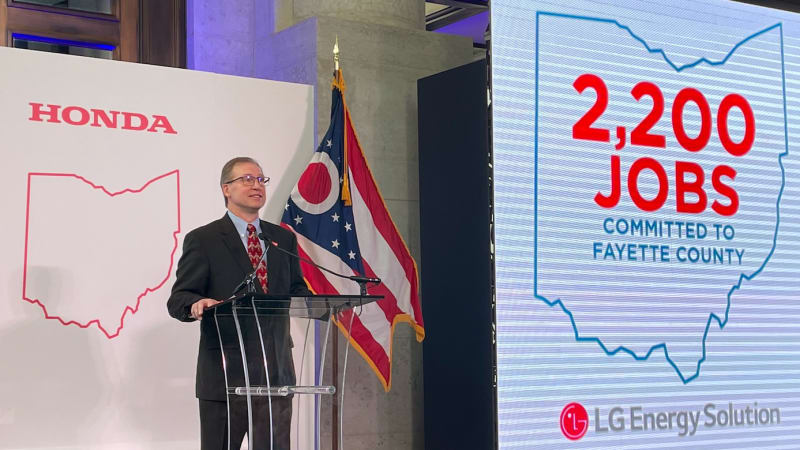

Honda Executive Vice President Bob Nelson announces the automaker’s plans for a $3.5 billion joint-venture battery factory in rural southern Ohio earlier this month. (AP)

WASHINGTON — Heading into next week’s midterm elections, many Republican candidates are seeking to capitalize on voters’ concerns about inflation by vilifying a key component of President Joe Biden’s climate agenda: electric vehicles.

On social media, in political ads and at campaign rallies, Republicans say Democrats’ push for battery-powered transportation will leave Americans broke, stranded on the road and even in the dark. Many of the attack lines are not true — the auto industry itself has largely embraced a shift to EVs, for instance, and some Republican lawmakers are quick to cheer the opening of EV battery plants in the U.S. that promise new jobs.

But political analysts say the GOP messaging exploits voter hesitancy on EVs that may have put Democrats on the defensive at a time when Americans are especially feeling a financial pinch.

More than two-thirds of Americans say they are unlikely to purchase an electric vehicle in the next three years, according to a new poll by The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research. Democrats are twice as likely to say they plan to purchase one as Republicans, 37% to 16%, respectively.

“There’s still lots of selling to do before EVs catch on with the American people,” said Jim Manley, a Democratic strategist and longtime staffer to the late Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev. He described early Democratic messaging suggesting that EVs were an immediate solution to rising gasoline prices as a mistake. “That creates an opening for Republicans in this election, which begins and ends with the economy and inflation.”

In a key Iowa House race, an ad by a Republican-aligned group features a man standing beside a pickup truck as he calls Democratic Rep. Cindy Axne and the Biden administration “clueless and out of touch” for supporting electric vehicles with batteries currently made in China.

In competitive Nevada, GOP Senate candidate Adam Laxalt mocks Democratic Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto’s support for her party’s sweeping climate and health law, which includes tax credits to purchase EVs. Laxalt warns that Nevada drivers will have to forgo charging their EVs during extreme heat to avoid straining the power grid.

The issue has also become a flashpoint in governors’ races in states such as Michigan, Minnesota and California, where Democratic incumbents have defended their support for a rapid transition to EVs — California set a goal for all new vehicles to be electric or plug-in hybrid by 2035 — and grappled with questions over how to pay for charging stations and road upgrades as gasoline tax revenue begins to decline.

Even with higher gasoline prices, the inexorable march to an all-electric future faces challenges, none of which will be resolved before the midterm elections that will decide control of a closely-divided Congress.

Hindered by supply chain shortages and manufacturing that currently depends on battery parts made mostly in China, electric vehicles cost an average $65,000 and remain out of reach for most U.S. households. That has Republicans hitting harder on prices — former President Donald Trump riffs frequently that EVs will lead to the demise of the U.S. auto industry — and Democrats talking up recent drops in gas prices and jobs created by EVs and other clean energy. House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy pledges an agenda of increased U.S. oil drilling and undoing Biden’s climate and health law if his party retakes the chamber.

As president, Biden racked up congressional wins that included sending $7.5 billion to states to build out a national highway network of up to 500,000 EV charging stations. Democrats’ climate and health law also extends tax credits of up to $7,500 starting next year to consumers to purchase EVs.

Autotrader analyst Michelle Krebs said EVs are a hard sell during the campaign because they remain a distant future for most Americans. Unlike stimulus checks in 2020, the tax credits for EVs in Democrats’ climate and health law are still being sorted out and could ultimately leave few Americans eligible. Currently, EVs make up about 5% of U.S. new vehicle sales.

“Not everybody sees EV charging stations in their neighborhoods right now, so that has an impact,” she said.

In an interview, White House infrastructure adviser Mitch Landrieu said the high price of EVs — including up to $400,000 for an electric school bus — is “a legitimate criticism,″ but added: “The more of these we make, the cheaper they are going to get.″

General Motors, Ford, Toyota and other carmakers have pledged to ramp up EV production dramatically, he said, and as they do EVs will “become more affordable.” GM, for instance, plans to start selling a compact electric Chevrolet SUV next year with a starting price around $30,000.

Gregory Barry, 45, a Republican father of two in Audubon, Pennsylvania, says he’s open to electric vehicles once they become more affordable and take less time to charge but says it’s a mistake for the U.S. to ignore oil and other energy sources in the meantime.

Dissatisfied with Senate GOP candidate Dr. Mehmet Oz on other issues, Barry said he ruled out voting for Democrat John Fetterman over his seemingly contradictory positions on fracking and will likely cast a ballot for a third-party candidate.

Meg Cheyfitz, a 67-year-old self-described progressive in Columbus, Ohio, worries about climate change and believes the government isn’t doing enough to tackle the problem. But she has no intention of buying an EV, saying she and her husband can’t easily install a charger at home since they park their cars on the street. Cheyfitz also believes EVs remain a relatively unknown technology with potentially mixed effects on the environment.

“Tax credits for EVs aren’t enough,” said Cheyfitz, who voted for Democrats on the ballot during early voting but says she won’t back Biden if he runs in 2024. “I don’t really see them taking meaningful action at all on climate.”

Environmental groups dismiss the notion that the issue of climate change has gotten lost in the midterm elections, citing recent White House announcements highlighting billion-dollar private-sector investments in domestic manufacturing of batteries for EVs as well as $1 billion in federal spending for electric school buses. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen hailed a new “battery belt” in the Midwest, and Vice President Kamala Harris traveled to Washington state to promote the purchase of 2,500 “clean” school buses under a new federal program.

In some states, support for EVs is bipartisan. Georgia Republican Gov. Brian Kemp has been embracing big investments by Hyundai and Rivian to build EV plants in his state in his reelection fight against Democrat Stacey Abrams. Democratic Sen. Raphael Warnock is running an ad in his race against Republican Herschel Walker that features the incumbent riding on an electric school bus. “Get on the bus, the bus to the future,” Warnock says, extolling the thousands of jobs at a Georgia company that makes electric school buses.

In Ohio, Republican Senate candidate JD Vance opposes a $3.5 billion joint-venture battery factory planned by Honda, part of a wave of U.S. battery and EV assembly plant announcements aimed at boosting the domestic supply chain. The plant is expected to create 2,200 jobs. Vance instead is promoting increased use of natural gas. Democrat Tim Ryan’s campaign criticizes Vance’s opposition as a sign he “has no idea what’s happening in Ohio when he rails against our rapidly growing electric vehicle industry.”

Katherine García, director of Sierra Club’s Clean Transportation for All campaign, said the U.S. is “at a turning point for electric vehicle adoption,″ adding that the new climate law “is going to be a game changer for climate action.″

“This administration and this (Democratic) Congress have really delivered on climate, and we need it to continue,″ she said.

___

AP polling director Emily Swanson and AP writer Jill Colvin in Washington and auto writer Tom Krisher in Detroit contributed to this report.

___

Follow the AP’s coverage of the midterm elections at https://apnews.com/hub/2022-midterm-elections