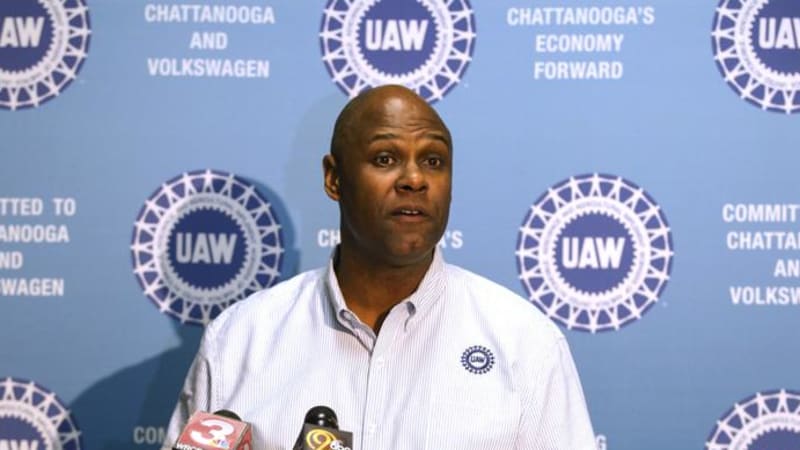

DETROIT — Ray Curry is taking over leadership of the United Auto Workers perhaps the most critical juncture in the union’s history.

The UAW’s International Executive Board on Monday named Curry, its secretary-treasurer, as union president, replacing Rory Gamble, who retires on Wednesday.

As soon as he takes over the 397,000-member union on Thursday, Curry will face extreme challenges in just about every direction. The UAW is coming out of a bribery and embezzlement scandal that sent two former presidents to prison, and it’s operating under a court-approved monitor who can veto financial decisions. Members are skeptical about their leadership.

There also are questions about safety protocols as the coronavirus pandemic wanes, and about shortages of critical parts such as computer chips that have crimped auto production by forcing plant shutdowns.

The auto industry, where most of the UAW’s highest-paid members work, is undergoing a seismic shift from internal-combustion to electric vehicles, placing thousands of jobs making gas-powered engines and transmissions in jeopardy.

Detroit automakers are forming joint ventures to set up new battery plants that the union will have to organize. And it will probably try to unionize new battery factories in the South. Since electric cars have fewer moving parts, automakers will need about 30% fewer workers to assemble them.

“I can’t even imagine a time with more change than we’re dealing with,” said Kristin Dziczek, senior vice president at the Center for Automotive Research, an industry think tank in Ann Arbor, Michigan. If the union can’t organize Southern battery factories, it won’t be able to set wages in that business like it has done in auto manufacturing, she said.

Curry, 55, has only about a year to distance himself from the corruption and convince members he’ll get the union on track. Sometime before November, members will vote to decide whether they want to directly elect their leaders instead of the current system in which leadership is chosen by delegates to a convention. If they agree to direct elections, those will have to happen before June 30 of next year.

“This transition now gives Curry and this team a year basically before the convention to get a track record, to get some experience with the members about how they will lead,” Dziczek said.

In his statement Monday, Curry acknowledged the challenges and said the union can handle them.

“Industry is at a crossroads right now with massive changes in new innovative technologies,” he said. “It will be up to us to navigate through this monumental shift in mobility and manufacturing.”

Gamble was the union’s first Black president, and Curry will be the second. He will be replaced as secretary-treasurer by Frank Stuglin, 61, who now is director of a union region covering the Detroit area.

Curry, the union’s fourth president in three years, said he would continue to build on a commitment of transparency, reforms, and checks and balances in the wake of the scandal. He said he would work with Gamble to make the leadership transition smooth.

Eleven union officials and a late official’s spouse have pleaded guilty in the corruption probe since 2017, including the two presidents who served before Gamble, Gary Jones and Dennis Williams.

Matthew Schneider, the former U.S. Attorney in Detroit who led the investigation, said the corruption was so deep that the federal government may take over the union.

But Gamble agreed to financial safeguards and a court-appointed monitor to oversee operations for six years, as well as the election for members to decide if they want to vote directly for leaders.

Curry doesn’t come from the traditional leadership path that begins at one of the Detroit automakers. He joined the UAW in 1992 as an assembler at Freightliner Trucks in Mount Holly, North Carolina, and worked his way up to regional director in the South.

He negotiated new labor contracts with numerous auto parts makers, and helped to organize Freightliner factories in North Carolina, according to his biography on the union’s website. He also led the union’s move into casinos in 2015 when the UAW successfully organized workers at the Horseshoe Casino in Baltimore.

Curry was named secretary-treasurer at the union’s convention in 2018, replacing Jones, who became president. Earlier this month Jones was sentenced to 28 months in federal prison.

Curry’s background of organizing and knowledge of the South could be plusses for the union, Dziczek said. Although it has had trouble organizing Volkswagen and Nissan factories in the South, under Curry it has had success in unionizing parts suppliers and heavy-truck factories, she said.

Curry has been the top union official involved in a long-running strike by 3,000 workers at a Volvo truck plant in southwest Virginia. Workers have twice rejected six-year tentative agreements negotiated by their leaders and returned to the picket lines in early June.

Dziczek said the nation is now in a post-pandemic “take-this-job-and-shove-it” mentality, with workers changing or leaving their jobs. This could work to the union’s advantage in organizing, she said.

The executive board also picked Chuck Browning, director of another Detroit-area region, to become vice president. He’s likely to replace Gerald Kariem, who stepped down as the vice president dealing with Ford Motor Co.